reclaiming medusa

from ancient mythological monster to modern day feminist icon, this is the ultimate retelling

A few of you asked for a more in depth look at Medusa as a feminist icon after the newsletter I wrote on her back in November last year (how was that three months ago already!), so here she is. I’m sorry it’s taken so long, I really wanted to do this piece justice to be honest.

You can read my initial newsletter about the Medusa myth here.

I wondered if this essay would have enough substance when I set out to plan it, but it quickly became clear just how relevant Medusa has been to the feminist movement in recent years. I had so much fun researching for this one. A lot of it was drawn from my uni studies which, here, I was able to dive deeper into when I wasn’t allowed two years ago, due to pesky word counts and the like.

If you asked most people about Medusa, even now, they’d probably describe a terrifying woman with snakes for hair who can turn men into stone with a single look. She’s been a staple of mythology and pop culture for centuries, from ancient Greek pottery to the literal Versace logo. In recent years, however, she’s been reinterpreted, not as a monster, but as a symbol of female empowerment, rage, and persistence against patriarchal violence. This transformation has positioned our girl as a key figure in new, feminist mythology and modern gender discourse.

I know I shared my newsletter on the myth above, but if you don’t have time to read it or just don’t fancy it, I’ll give a quick run-down here too.

The most famous version of Medusa’s story comes from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, written in the first century AD. According to his version of the myth, Medusa was originally a beautiful mortal who caught the eye of Poseidon. He raped her in a temple of Athena, and instead of punishing Poseidon, Athena transformed Medusa into a Gorgon, giving her snakes for hair and a gaze that turned men into stone.

Plenty to be angry about.

In short, this is a story about a woman being punished for her own victimisation. Medusa, rather than being protected, was turned into a monster, shunned and feared. A survivor of sexual violence being blamed and discredited rather than protected and supported.

Sound familiar? The myth of Medusa, one which exists at least as far back as two-thousand years ago, reflects the struggle of women in patriarchal structures, making her an undeniable feminist symbol.

For centuries, however, Medusa existed as a depiction of terror, a warning against rather than for female power. Sigmund Freud even suggested that the image of Medusa’s head represented male ‘castration anxiety’ (men finding powerful women intimidating). But feminists in the twentieth and twenty-first century have flipped that interpretation on its head… no pun intended.

Hélène Cixous, a French feminist writer, playwright and literary critic emphasised in her 1975 essay The Laugh of the Medusa that women need to embrace their power and refuse to be silenced. Instead of seeing Medusa as a monster, she saw her as a representation of female strength, rage and defiance. Cixous was one of the earliest thinkers in post-structural feminism, and the use of Medusa in the title of her famous essay isn’t a coincidence.

“You only have to look at the Medusa straight on to see her. And sheʼs not deadly. Sheʼs beautiful and laughing...” - Hélène Cixous, The Laugh of Medusa.

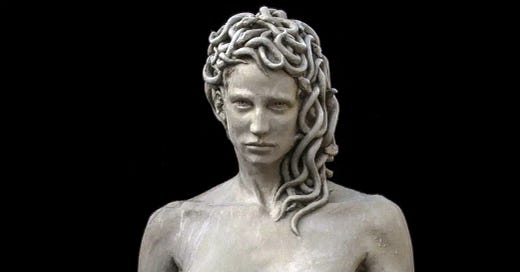

Medusa has been rebranded in modern media, fashion and art, adopted by luxury fashion brand Versace as its logo to symbolise beauty, strength and allure. The most striking use of Medusa in art in the last twenty years though is, for me, a sculpture by artist Luciano Garbati. Cast in 2008, the sculpture Medusa with the Head of Perseus went viral in 2020, and I adore it. It is a striking visual representation of a reclamation of power, and resurfaced to the algorithm along with the phrase: “Be thankful we only want equality, and not payback.”

“The representations of Perseus, he’s always showing the fact that he won, showing the head… if you look at my Medusa… she is determined, she had to do what she did because she was defending herself. It’s quite a tragic moment.” - Luciano Garbati

This image was reused during 2017 (this one a parody of Cellini’s original statue): a truly disgusting use of Photoshop showing then (and, depressingly, now again) President Donald Trump as Perseus holding the severed head of Hillary Clinton as Medusa, in a stark example of how powerful women are often symbolically, or here, literally depicted as being defeated. The image echoed historical narratives of men triumphing over women they perceived as threatening, reinforcing the deep-seated fear of not female leadership, but female autonomy in general.

Throwback to when I did my presentation on Medusa during the second or third month of my Classics MA, put the Trump/Clinton picture on the board, and a guy in that class laughed loudly and said ‘HAH. I want that on a t-shirt’ and then all his friends laughed too.

And then I quit !! Anyway.

Natalie Haynes’ 2022 novel Stone Blind (you know I had to bring it up) has given Medusa’s story further light, centring her perspective rather than the ‘hero’ who murdered her. This modern retelling (as with Jessie Burton’s Medusa) challenges the idea of Medusa as a villain and instead highlights her as a woman whose story was twisted to fit a patriarchal narrative.

In Greek mythology, Perseus is celebrated as the hero who beheaded Medusa, using her severed head as a weapon before giving it up to Athena. When examined through a feminist lens (or any other lens, frankly), however, Perseus can be seen to represent the patriarchal force which aims to silence/control powerful women. His act of slaying Medusa mirrors the way in which women throughout history have been vilified, punished and erased for challenging male dominance.

So Perseus slaying Medusa is not an act of heroism, but is in fact a symbolic act of suppressing female rage and bodily autonomy. Her head, once a source of male terror, is repurposed by the same men who so feared her as a tool of power, much the same as women’s voices and bodies are controlled and commodified in our patriarchal society.

The reversal of power in modern interpretations such as Garbati’s Medusa with the Head of Perseus reflects an important shift towards equality and away from the structures which have historically sought to suppress it.

Medusa’s transformation from monster to feminist icon is part of a broader cultural shift. Crucially, we’re re-examining the stories we’ve been told and questioning why certain figures, especially women, are cast as villains (hence the birth of Ancient Echoes). Her story is no longer just a cautionary tale: she’s a symbol of defiance, of strength in the face of injustice, and in a world which is still punishing women for their own pain, Medusa’s legacy remains a vital part of the feminist discourse.

In today’s era of gender-based violence awareness and women beginning to reclaim their voices, Medusa as a symbol of survivors fighting back and reclaiming their power resonates more than ever.

Medusa is no longer a myth, but a movement.

Or, in other words…

I mean, Perseus is still acting out of heroism. You can have empathy for Ovid’s version of Medusa and recognize her importance in feminism without dismissing the earlier myth (since the archaic period, she was first and foremost a monster who had never been a woman, never been punished, and who consensually laid with Poseidon) and without acting as if Perseus killed her because he was selfish and patriarchal, when he was literally a young boy trying to save his mother from a forced marriage because a king had randomly decided he wanted her even if she was unwilling (and then saved a young girl from human sacrifice)

Haven't read Stone Blind but I have read Natalie Haynes' very thoughtful essay on Medusa in her book Pandora's Jar, which was both enjoyable and an eye-opener for me. (One thing I came across lately - you are probably already aware of it - was a piece by Jasmine Sun on how the post-literate society is providing us with 'heavy' characters (Trump and Musk, for example) not unlike characters from Greek mythology: https://substack.com/home/post/p-155295384)