let's talk about virgins !

the price of untouchability in the ancient world

This week I finally had some much needed time off and have been reading Emma Southon’s ‘A History of the Roman Empire in 21 Women’ which is hilarious, very readable and extremely informative, so if you’re interested and haven’t read it yet I would recommend giving it a shot! I’m only about seven chapters in, but I’ll bet the rest of the book is going to be equally as fabulous.

Anyway, there was a chapter on Vestal Virgins, who I kind of vaguely knew about but as an ancient Greece gal wasn’t too sure on in terms of writing about them (hence why I’m reading the book). And that got me thinking about virginity in the ancient world and what it meant for women, and here we are!

In ancient myth, virginity is like a strange sort of superpower which, at a glance, elevated a woman to make her sacred and revered. But upon closer inspection this ‘privilege’ starts looking a lot less appealing and a lot more like a gilded cage, which is what I’m going to discuss in this article.

But first, this tweet:

It just seemed on theme and I laughed so hard the first time I came across it. Anyway.

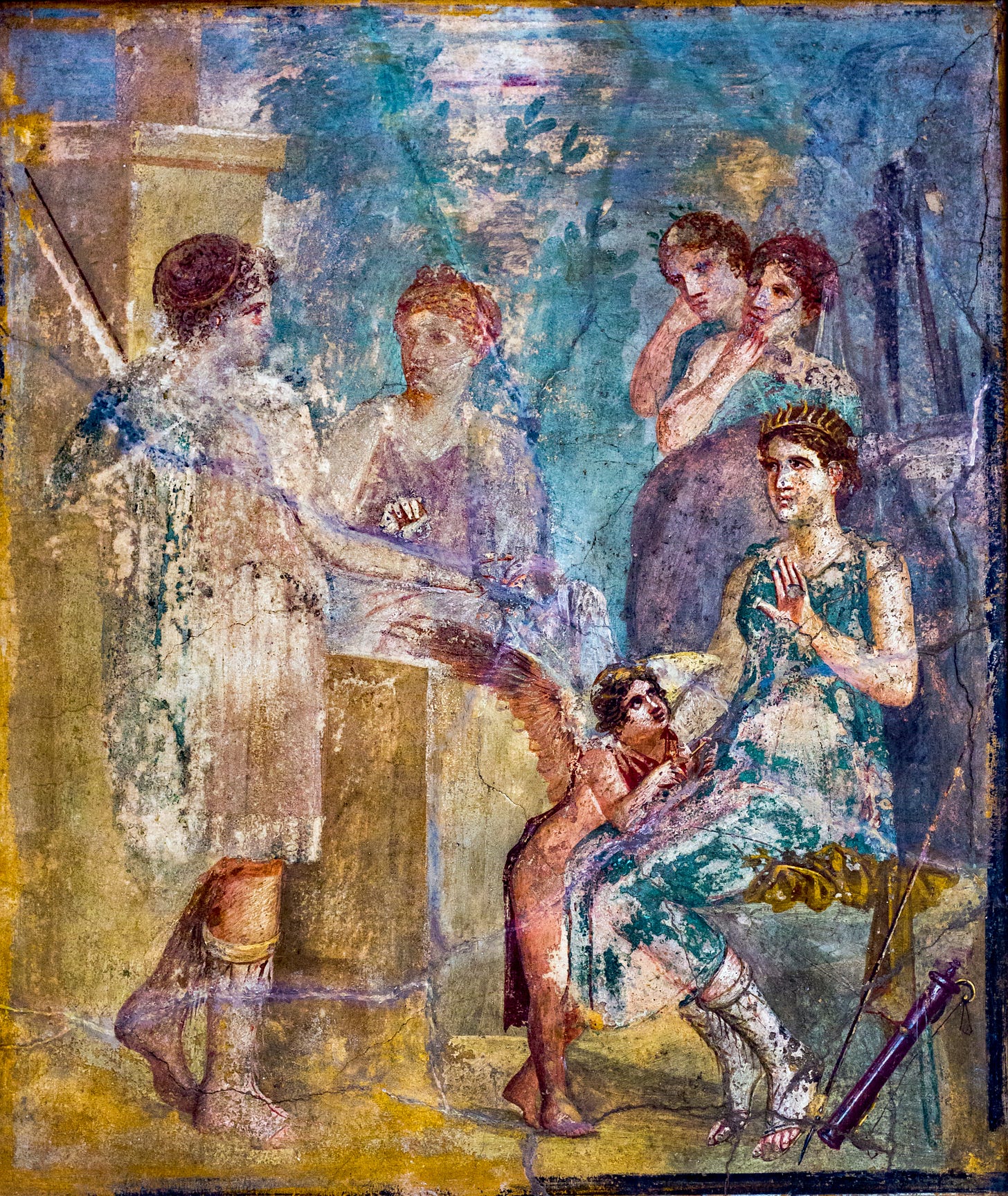

Some of the most powerful women in Greek and Roman mythology were those who remained virgins, including literal goddesses such as Artemis, Athena and Hestia, and the Vestal Virgins of Roman society. The latter held a place of enormous prestige, but the price was immense pressure. Their untouched, ‘pure’ bodies were viewed as essential to the survival of Rome itself.

I feel like it’s quite easy to romanticise these virgin goddesses as symbols of independent queens, but these aren’t really stories of sexual freedom. They’re more about what happens when women’s power is allowed… only when there’s a caveat. In this case: them remaining virgins.

Artemis

Artemis (or Diana, if you were a Roman), is often framed as a feminist icon. Independent, living with her girlfriends in the forest away from the reach of men, moving through the land on her own terms. Sounds like a pretty good deal, no??? She protects young girls who swear off men and vow to stay virgins forever, punishes those who violate her sacred boundaries and stays firmly in control of her own body.

Her myth, however, is steeped in violence. When the hunter Actaeon accidentally comes across her bathing naked in a spring, she transforms him into a stag and has him torn apart by his own hunting dogs. Talk about savage. Similarly, when Orion tries to claim her, he ends up dead as well.

So Artemis’ virginity isn’t solely a personal choice, it’s a line drawn very physically, in blood. Her power and autonomy is conditional on her remaining distant and terrifying, and thus untouched.

It’s hard for me, and perhaps most modern readers, however, not to picture Artemis and her girls running free in the forest living their best cottagecore lesbian lives, laughing at the idea that they’re all ‘pure and chaste’ just because the men weren’t invited.

But maybe that’s just me, idk.

Athena

Athena (Minerva, if you’re Roman) born directly from Zeus’ head clad in full armour (don’t ask), is another virgin goddess, but I reckon her story reads more like a strategic rebrand than anything else.

She is the goddess of wisdom and battle, often favouring male heroes (Odysseus, Perseus, Achilles – but never romantically!) over female figures (like Medusa, who she cursed for being raped by Poseidon in her temple). Her virginity places her above the emotional bodily realm traditionally associated with femininity. She is a symbol of reason, logic and discipline: qualities the Greeks primarily aligned with, of course, masculinity.

Athena’s virginity serves solely to neutralise her womanhood so that she can enter male domains (politics, war, philosophy), precisely because she has symbolically left her gender behind. And she remains able to do so only as long as her modesty remains intact.

We know that Athens was named after the goddess Athena, but it’s worth noting that her temple the ‘Parthenon’ actually comes from the Greek word Parthenos, meaning virgin, which reflects Athena’s epithet as Athena Parthenos. ‘Athena the Virgin’.

Hestia

Hestia (or Vesta, important for the next section!) is probably the most overlooked goddess in the pantheon, so much so that she is oftentimes completely replaced by Dionysus in the big twelve. She is goddess of the hearth, the flame at the centre of every home and temple, and never marries or engages in any kind of scandal, which explains why she so rarely appears in any Greek myth retellings.

She represents peace and domesticity, but also silence in a role which is absolutely foundational, but very much brushed over. I include her because she represents a recurring pattern in these myths: the more virtuous and controlled a woman tends to act, the less space she takes up in the narrative.

Which leads me neatly onto our Vestal Virgins.

Vestal Virgins

In ancient Rome, the Vestal Virgins were chosen as children and sworn to thirty years (yep, you read that right) of chastity in service of the goddess Vesta (Hestia). They were responsible for keeping the sacred fire burning 24/7 in Vesta’s temple, and if it went out it was believed that Rome would fall.

It is a subject of great debate and confusion just why these Vestals had to be virgins. Was it because the fire was so pure, that the girls tending it had to be pure too, lest they corrupt it? All anyone knew was that their continued virginity was of absolute and utmost importance to the continued welfare of the entire Roman Republic, so we’ll leave it at that.

If any of these girls broke their vows, which two did, they were buried alive in the walls of Rome and left to die. Here, Southon brings up a quote from Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, who coined the phrase ‘well-behaved woman seldom make history’. These women would have been shamed in their lifetimes, but we don’t know any more details about other Vestal Virgins except from some of their names.

The two Vestals who were buried alive, Oppia and Urbina, have had their stories told, unlike their well-behaved peers who would have been praised in their lifetime and never spoken about again. But at what cost? That was a bit of a tangent, but it was a cool one so I think it’s allowed.

Thank you Emma Southon!

Point is, Vestal Virgins were honoured and well looked after, but their value hinged entirely on their purity. They were simply symbols of a moral ideal that wasn’t about them as women at all, and again, their worth came with conditions.

So what?

Virginity allows these women power, but only within narrow boundaries. It’s never about choice, but containment: a tool to render women non-threatening and convenient for the narrative. This is a legacy which still, troublingly, echoes today. Quite loudly, in fact.

Our society still expects women to be either powerful or desirable, and associates restraint with virtue. We still place value on women’s perceived purity, whether through the policing of sexuality or the persistent double standards around desire. You need to look no further than the backlash Sabrina Carpenter is currently receiving, which is highly reminiscent of Britney Spears’ experience in the public eye.

The virgin/whore binary may seem subtler now (unless you’ve ever been hit on by a drunk guy in a nightclub and turned him down), but it’s very much alive in media, politics and the language we use to describe women every day.

These stories tell us a fair bit about how women’s power has always been shaped by what they aren’t allowed to do. They’re worth revisiting/retelling not because they tell us about how things used to be, but because they show us how scarily little things have changed over time, and what it might mean to finally break free from this patriarchally palatable bargain.

Such a great read! Your point that the price of power is untouchability and a rejection of one's femininity is so poignant. On the other end of the spectrum, ancient Greeks and Romans celebrated live male nudity and sexuality. Men consolidated their power BY having sex. It's wild how little these notions have changed over time.

In the Early Modern obv Queen Elisabeth I, after whom Virginia was named. Certainly Powerful. Her chasteness has been questioned but never disproven.